Thailand’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) was finally approved in February 2019 by the Thai National Legislative Assembly, after several legislative attempts. The PDPA was published in the Royal Thai Government Gazette following the passage of the bill, and came into effect on May 28, 2019. Organizations now have one year to fully comply with their policies by May 27th 2020.

Overall, the PDPA will change Thailand’s data protection landscape as this is the country’s first comprehensive legislation on the issue. Many of the standards and responsibilities under the PDPA have been adapted from the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), reflecting Thailand’s expectation of obtaining a European Commission decision on adequacy. The implementation of this legislation by Thailand has been partly inspired by many GDPR standards, and will significantly increase privacy protections for Thailand-based companies. Although an official English translation of the PDPA is not yet available, companies working in Thailand or handling Thai personal data will need to get to know this law quickly before its implementation date, which is less than a year away.

Overview

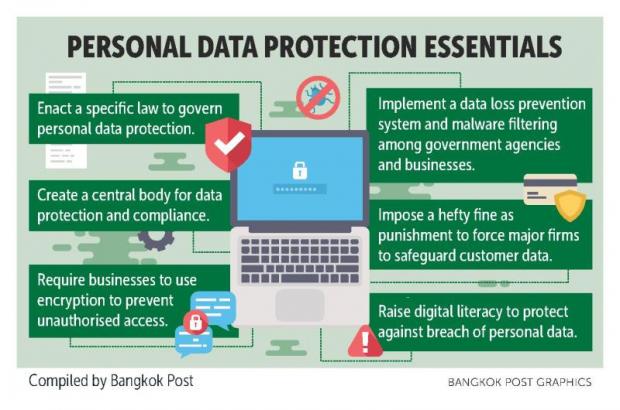

Similar to the GDPR, the purpose of the PDPA is to protect data proprietors (i.e. data subjects under the GDPR) in Thailand from unauthorized or illegal collection, use or release and processing of their personal data. The PDPA applies to non-Thailand organizations that either provide products and services to Thailand individuals or monitor individual behavior in Thailand. The legislation is expected to have a significant effect on non-Thailand-based online service providers, who hope to continue serving the Thai market.

The GDPR borrows a variety of criteria from Thailand’s PDPA. First, the law sets out a series of legal bases that entities must use to process information from data owners. These legal bases, like the GDPR, include agreement, legal obligation, public interest, and legitimate interest. However, individual rights under the PDPA are quite close to those found under the GDPR, covering the right of access, content, erasure and rectification. And eventually, like the Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) of the GPDR, the PDPA must set up a Personal Data Protection Committee (PDPC) to enforce the law and provide guidance to help companies ensure that the PDPA complies. Let’s look at the main criteria and concepts found in the new legislation in Thailand.

Key Definitions

The specified terms used in the PDPA are generally consistent with other GDPR-inspired legislation, further suggesting that Thailand may be following an EU-inspired agreement.

Personal Data: Broadly defined as information that can identify an entity directly or indirectly, excluding data from a deceased person and private business data such as contact information, names, or addresses.

Data Controller: A person or agency allowed to decide on the collection, use or disclosure of personal data.

Data Processor: A person or organization that gathers, uses or discloses personal data according to the data controller’s orders.

What is Sensitive Personal Data?

The PDPA sets out stringent requirements for the collection and preservation of sensitive personal data, including personal data relating to:

racial or ethnic origin

Political opinions

Religious or philosophical convictions

Criminal records

Trade union memberships

Genetic data

Biometric data

Medical records

Sexual orientation or preferences

Collection of confidential personal data is illegal, except in certain cases, such as medical emergencies or as required by law, without the express consent of the data owner.

Rights of Data Owner

The subject rights under the PDPA match those in the GDPR. Under the PDPA, Thai data owners will have the right to request access to their personal data and may make requests for the deletion, destruction or anonymisation of their personal data.

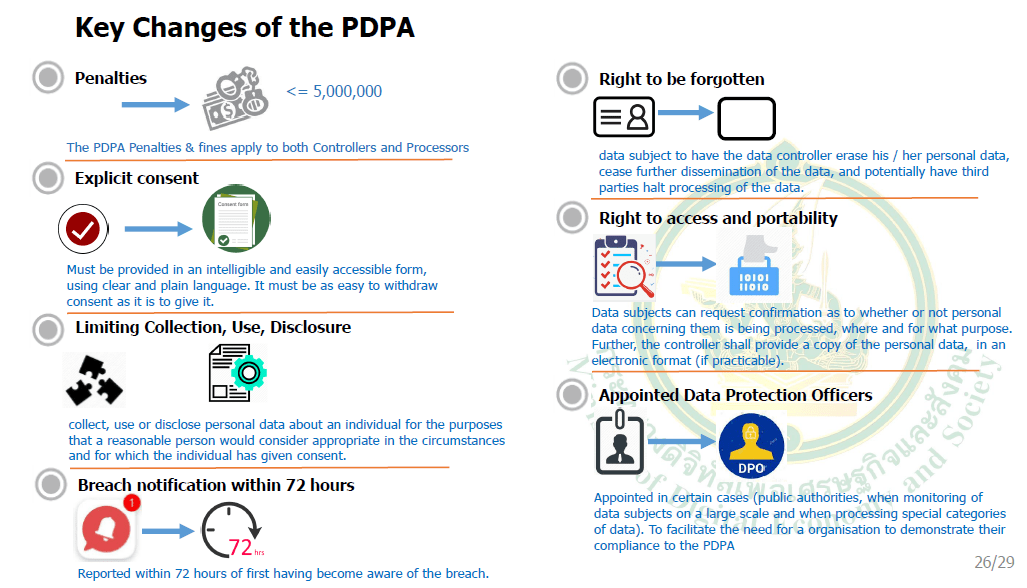

Consent Requirements

Consent Requirements The PDPA specifies that direct, express consent must be obtained on or before the collection of personal data (whether in writing or through an electronic system), and that the requests should not be false or deceptive. Data owners may revoke their consent at any time, but the revoke can not impact the previous compilation, use or release of legally consented personal data. The exemptions from the conditions for consent are quite broad, covering contractual obligations, public interest and rational reasoning.

To minors the PDPA requires parental consent to data owners under the age of 10 (and in specific circumstances for minors over the age of 10), whereas in GDPR, all children under the age of 16, requires parental consent.

Enforcement and Penalties

The implementation of the PDPA must fall under the jurisdiction of a Committee for Personal Data Protection Committee (PDPC), formed to enforce compliance. The PDPC will be developing recommendations for the introduction of a data protection framework.

Organizations will face both civil and criminal penalties if found non-compliant. Total PDPA penalties will be large (though not as extreme as the GDPR), with each violation having the potential to incur administrative fines of up to TBH 5 million (US$ 165,000) and criminal fines of up to TBH 1 million (US$ 33,000). The PDPA also gives the court the power to pay punitive damages up to twice the amount of actual damages and up to one year’s imprisonment. Additionally, it is now possible for data owners to pursue their own class action lawsuits.

Cross-Border Data Transfers

Under the PDPA, criteria for cross-border transfer are only broadly specified which increases the risk of enforcement.

The PDPA would require one of three conditions for international transfers:

- Transfer to a country which has developed strong data protection measures in line with the guidelines laid down by the Personal Data Protection Committee

- Consent

- Pre-existing relationship between data controller and data owner

Data Protection Officer

Similar to the GDPR, data controllers or processors gathering, using, tracking, and releasing vast amounts of personal data will need to name a Data Protection Officer (DPO) to track and check compliance.

Preparing for Compliance

Given the short enforcement grace period, it is important that companies begin to review their activities related to personal data (e.g. data of customer, supplier, employee, billing and payment, etc.) and take the necessary steps to ensure that PDPA policies comply with all these requirements, by 27 May 2020.

- Data mapping to explain the collection, processing, dissemination and storage of your company information, including the definition of the legal basis for personal data collection and use

- Review of internal policies, agreements and practices regarding personal data

- Implementation of data management and operating systems

- Updating existing privacy records and producing relevant legal documentation

- Ensure that managers and personnel are fully trained in the PDPA criteria

- Conduct a gap assessment to evaluate existing enforcement rates

- A process in place to exercise the rights of individuals with regard to their personal data

And with significant penalties for non-compliance and less than a year to the deadline, companies managing Thailand’s data owners ‘ personal data should not wait to start compliance work.